Chicago Union Stockyards, 1947

Animal infrastructures are tied directly to larger forms of control and management which correspond to important shifts in architectural history. The production of animals within modern industry, from the stockyards immortalized in Upton Sinclair’s Jungle to the ultra anesthetized contemporary German animal-husbandry models, may undergo historical periodization yet the brutality at the heart of modernity remains the same. This report– a spatial genealogy of the feedlot– will first begin with the birth of managerial urbanism and the tactical architectures of modernity.

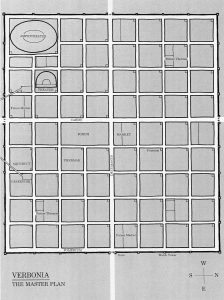

The prehistory of planning and managerial urbanism can be traced to the Roman urban plan which promoted visible order. The foremost influences of Roman architecture took cues from functionalism and imperialism, where philosophy, art, and literature played an important role in the development of the Western interior. Roman town planning originated from the military encampment, and the formulaic order of the Roman castra, as James C. Scott illustrates in Seeing Like A State. The Roman army utilized a gridded structure of the camp for efficient internal communication as well as its easily reproducible logic. Of these architectures of visibility developed by the Romans, some of the most important architectures of political subjection were the forums at the center of Roman urban life. The forum was the cultural center where political, economic, administrative, social and religious activities were located, and where citizens could map themselves into the structure of the state.

Some of the most developed forms of Roman public life growing out of the forum included theaters, stadiums, and infrastructures of public utility (water, sewer, transport, defense, markets and public squares). While these sites of Roman governance were central to gain power and control through visibility, there was also the need to link cities through paved roads. The grid, gleaned from the Roman military camp, again satisfied the need to communicate and create reproducible knowledge of any point in the empire. Forums facilitated both communication and political control and were often placed at the intersection of important urban pathways. They were also often situated on river banks due to supply demands and where canals brought water to ports. Where infrastructure connected the empire, the forum synthesized and made legible the information being collected and distributed.

The height of the military-encampment-as-urban-model came during the modernization of Paris. Paris became the cutting edge of urban planning with its attention to a choreography of power flows. Baron Haussmann’s modernization program planned easily-surveilled boulevards for military troops to parade down while destroying medieval alleyways, which were metaphors of disease and the uncontrollable population. Lines of sight opened up through a unified urban landscape full of monuments and sites of symbolic power while speed and mobility of military power supplied the underlying spatial logic. Shifting our attention from the modernization of Paris we can see a similar mobilizing spatial logic unfold in Chicago, the center piece for American Westward expansion and modernity.

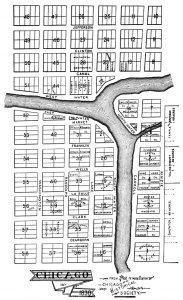

The pre-modern city of Chicago was a marsh swamp at the head of the winter-bound great lakes system. Fort Dearborn was built at the future site of Chicago on the water highway among Indian tribes, where early traders brought their goods. In this settlement, the first recorded slaughterhouse was built by Archibald Clybourn at the north branch of the Chicago river in 1827. Clybourn held a contract with the federal government to sell meat driven from the surrounding prairies and forests. While Cincinnati, St. Louis, and river towns in Indiana and Illinois were well established, Chicago’s development as a city in the 19th century took advantage of its location on the great lakes at the center of the United States. Its industrial prowess overcame any geographical hindrance of its particular locality by draining swamps and reversing the flow of the Chicago river, a major technological accomplishment. Surplus livestock were slaughtered at river towns all around the midwest then floated down rivers to markets or driven on foot and fattened near consuming centers. Some operations were conducted in the open, for instance– under the trees at the present site of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

As a landscape, Chicago drained resources from far flung regions and repurposed materials, machining the bounty of the prairies and forests into products for East Coast consumption. As a settlement, it tied vast swaths of the west together through rail transport and telegraph communications. The pastoral farm, the agricultural utopia of the pre-modern United States gave way to the industrial machine of Chicago and the industrial animal. And the center of Chicago’s machinic magnetism was the Union Stockyards.

The story of the Union Stockyards is largely a story of the development of transportation connecting productive agricultural regions. Private companies built toll roads to develop extensive land holdings in the western division of the city and taverns with stock pens were built by 1848. Livestock circulated through these taverns until 1852 and after the eastern railroads entered the city, lake shipping increased. Several slaughterhouses were built, yet lake and canal transportation could not compete with the railroads. Extensive facilities were constructed near the terminus of each railroad as it reached Chicago. Following the end of the Civil War, Chicago’s scattered livestock markets consolidated into one large market, the Union Stock Yard & Transit Co., on the South Side of the city. The tavern stockyards were, for the most part, not reached by railroad and most prominent stockyards located on tracks were owned by the railroads. They all closed a few days after the opening of the new Union Stock Yard in 1865.

The larger historical context of the Union Stockyards grew out of new opportunities and constraint imposed on emerging industrial systems. Modern mass production linked capital, raw materials, transportation networks, communications systems and skilled laborers along rail systems. Meatpacking was one of the first to implement rational production methods through which modernization on the farm could occur. The principals of rational management were considered industrial because the most prominent elements of this transition were technological and scientific innovations. Tractors, assembly lines, grain elevators, steam engines, rail roads, hybrid seeds, electricity, and pesticides revolutionized agriculture and did away with any superficial divide between the natural and the technological once and for all. Scientific rationality offered a solution to the mire of farm operations, unifying disparate elements such as crops, climates, economics, and politics into a single industrial unit.

Business leaders felt that agriculture should modernize along the same lines as modern factories to utilize the timeliness of machine operations, large scale production sites, mechanization, standardization of products and labor, routinization of the workforce, and efficiency. While interconnected and often sprawling, systems of agricultural production and consumption functioned like grids of hyper surveillance and rational control. Each innovation implemented relied upon another technology– credit systems, transportation systems, tax systems, legislative bases. It was the combination of science, technology, and rationalism that characterized industrial agricultural production as a kind of spatial techno-rationalism. Chains of bank credit, migrant labor, tractors, paved roads, commodity markets all combined in an interior architecture of industrial brutality. The Roman encampment had become a machine of consumption where life forms were abstracted and brutalized for market value.

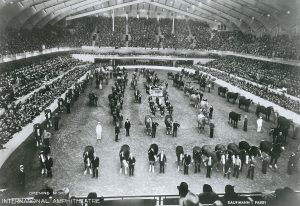

Not only did the Union Stockyards embody the technological apparatuses of its time, but it also operated on the level of subjection and spectacle. Just as the Roman forums had temples, civil buildings, engineering works and amphitheaters as spectacles, the stockyards were equally equipped. At the Stockyards, the Dexter Park Horse Exchange and Pavilion had an amphitheater and was capable of seating 3,000 people. The amphitheater was complete with a Sturtevant machine hot-air blast “for the most extreme weather.” These spectacles were later mobilized at the World’s Columbia Exposition in Chicago in 1893 where the public could see Muybridge’s Zoopraxiscope, a photographic device showing animals in motion, along with Edison’s Kinetoscope motion picture camera. They could also take guided tours of the Chicago stockyards. New technologies provided new modes of visual consumption where animals were not only produced as meat but also consumed as spectacle. The use of gelatin extracted from the animal still acts as a central ingredient of photographic and film stocks.

Interior architectures remain implicated in larger political-economic contexts of animal capital. The Union Stockyards operated at the intersection of modernity and brutality, hiding the costs of development through spectacle while making the exploitation of people, ecologies, and animals invisible within the everyday. Nearly doubling in size, the Stockyards annexed the Town of Lake in 1889 to avoid anti-pollution regulations. Ten years later, The Sanitary District of Greater Chicago reversed the flow of the river, allowing meat packers to sell manure and offal for fertilizer instead of dumping them in the river. The Chicago Health Department made many attempts to inspect the companies producing 80% of the country’s meat but were unsuccessful.

Within this machinic landscape, Upton Sinclair in 1906 illustrated the over crowding and lack of sanitation at the Union Stockyards where human mortality rates were highest. Antiquated sewers and the waste of 896,000,000 animals made Chicago pestilential creating an enormous public health risk. Foucault proposed that underlying this shifting dynamic was a deeper logic in which “the power to expose a whole population to death is the underside of the power to guarantee an individual’s existence.” From the tactical architectures of modernity tied to visibility and the management of populations, to the concern over public health and environmental regulations, Industrial Animal Architectures occupy a troubling site of infrastructural power. In the next report, we will look at the demise of the Union Stockyards, the rise of the Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFO) and the biopolitics of animal architectures.

___________

REFERENCES:

Deborah K. Fitzgerald. Every Farm a Factory: The Industrial Ideal in American Agriculture

Michel Foucault. The History of Sexuality Volume One: The Will to Knowledge

Illinois Historical Survey. Chicago Union Stock Yards

George Lambert. Chicago of Today: The Metropolis of the West

James C. Scott. Seeing Like A State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed

Nicole Shukin. Animal Capital: Rendering Life in Biopolitical Times

Upton Sinclair. The Jungle