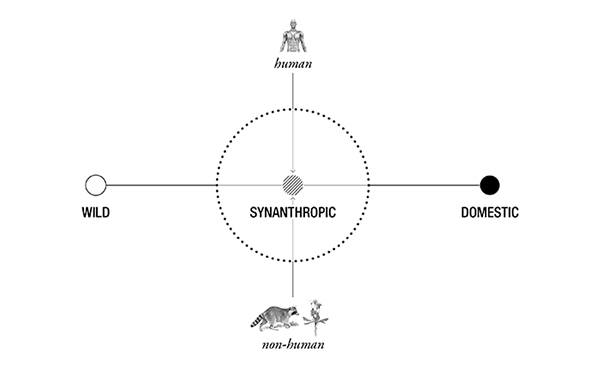

Humanity defines animals by their relationships to humans. Through this lens non-human species are categorized into two forms; domestic – dependent on humans for survival and augmented to live as companion species to humans, and wild – independent, capable of sustaining life without anthropogenic support. These relationships are based broadly on the level of human intervention required for an animal to survive.

The synanthropic condition lies within this emerging gradient. Synanthropes are species which exist between domestic and wild, who benefit from living in close proximity to humans yet remain beyond their control. These animals have evolved to the patterns of transformation, consumption, and production exhibited by human civilizations. As a result, these opportunistic species have thrived and proliferated alongside human geographic expansion. They are most abundant in city landscapes where they occupy the streets, buildings, and infrastructural systems established and inhabited by humans.

Urban development is creating opportunities for these species to adapt to the city. The rapidly transforming urban landscape leaves “ecological vacuums” that provide opportunities for species with high behavioral, demographic, and ecological plasticity to establish populations.[1] his ability to adapt and develop a commensal relationship with humans demonstrates that micro-evolutionary changes can occur within species over short time scales.[2] Maciej Luniak has defined this process as synurbization, the adjustment of wild animal populations to specific conditions of the urban environment.[3]

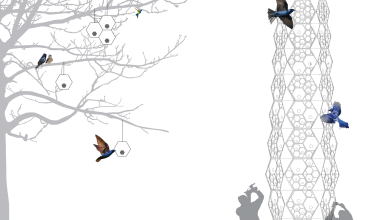

The synurbization process has enabled several bird and mammal populations to colonize cities, often with greater success than in their natural environment. This is because the urban environment offers a habitat with reduced predation risks, protection from climatic stresses, and year-round food abundance. Therefore the urban environment has a higher carrying capacity for select species than that of wilderness habitats.[4] The anthropogenic conditions of the city also alter species’ behaviours generally resulting in higher density populations, reduced territories and migration patterns, extended breeding seasons, changes in foraging behaviour, increased interspecies competition, and greater tameness towards humans.[5] Novel conditions also encourage species to act with ingenuity; to occupy unconventional building structures, appropriate human discarded materials for nests, and exist predominantly off of human refuse. Take for example the crows in Japan who weave stolen metal coat hangers together into nests, the raccoons in Toronto who have developed clever techniques for opening compost bins, or the birds who use cigarette filters to not only construct their nests and also ward off parasites.[6] By capitalizing on the opportunities presented within these novel ecosystems, birds and mammals are gradually adapting to urban life.

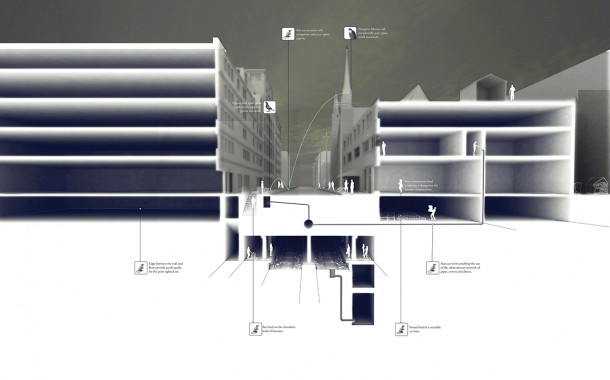

A prime example of a synanthrope is the brown rat. Historically, they have antagonized human populations by contaminating food supplies and spreading the Black Plague, and despite human efforts to eradicate them, they remain close cohabitants within our modern cities. How have they so successfully adapted to our shared environment? Brown rats are skilled climbers and swimmers, but also have a superhuman ability to chew through almost any material, enabling them to move through an urban maze. Since they have poor, dichromatic eyesight, they rely upon their keen senses of touch and smell to navigate space. A rat’s urban umwelt consists of a network of edges, masked in shadows, where heightened smells serve to guide it towards sustenance and safety. Subway tracks, sewer systems, and quiet basements are the playground for these nocturnal creatures.

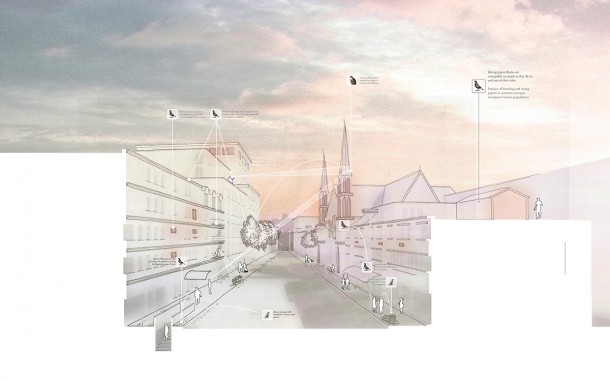

A pigeon however, views the same space through wide, monocular vision and in pentachromatic color. From their aerial position, the built environment registers as a series of ledges for perching and sunny parapets for warming during the cold of winter.

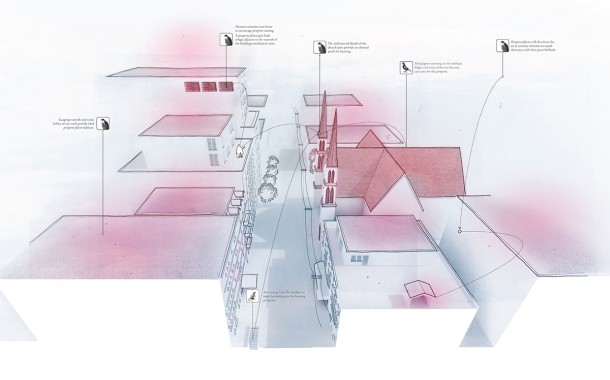

For the peregrine falcon, a recently adapted synanthrope, the city is a space of concrete cliffs and street valleys. Mechanical vents on tower tops, create heated nesting sites while pigeons below provide abundant sources of food. The urban ecosystem is a space of overlap of individual umwelts. We can begin to understand how animals successfully adapt to the urban environment by dissecting and representing the perceived environment of synanthropic species.

Synanthropes violate the once prevalent human conception of the city as a place without nature, and challenge us to re-examine the design of our shared urban environment. What if we reconsidered urban environments as diverse ecosystems? What if cities were planned to enable a greater diversity of species to cohabitate alongside humans? What if buildings were designed to welcome at-risk species to occupy their periphery? Coming to know the synanthropes which already occupy the city could provide clues in how welcome new species to inhabit the urban environment.

Drawings taken from Synanthropic Suburbia completed by Sarah Gunawan.

[1]Luniak, M. (2004). Synurbization – adaptation of animal wildlife to urban development (pp. 50-55). In Shaw et al., (Eds.) Proceedings 4th International Urban Wildlife Symposium.

[2]Luniak, 2004.

[3]Luniak, 2004.

[4]Shochat, E., Lepman, S., Katti, M., & Lewis, D. Linking Optimal Foraging Behaviour to Bird Community Structure in an Urban-Desert Landscape: Field Experiments with Artificial Food Patches. In The American Naturalist, 164,(2), 232-243.

[5]Luniak, 2004.

[6]Schwägerlis, C. (2014). Zooetiks #1: Sense, Sensors and Sensitivity [Powerpoint slides]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gt_101o9akM.